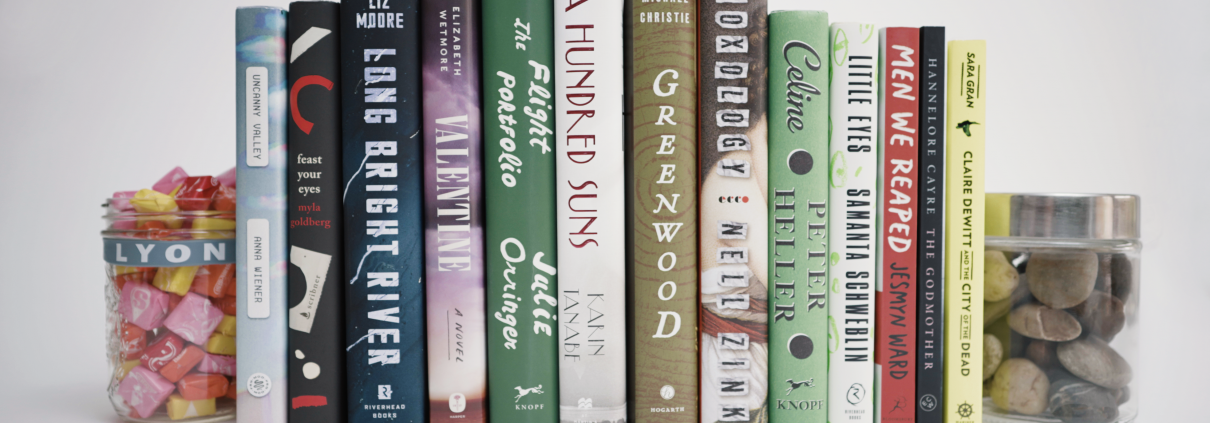

Summer Reading 2020

Even though we know you probably won’t be reading on a plane this summer and maybe not even on a beach, if you’re a reader, you’re likely still hungry for some more recommendations, and we like to oblige.

Uncanny Valley

by Anna Weiner

This one is a memoir of the author’s time in customer support in Silicon Valley. It’s a good companion piece to The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, written from the insider viewpoint. It’s also a good non-fiction take for anyone who enjoyed Dave Egger’s The Circle or Hulu’s recent limited series, Devs. Silicon Valley is a big part of our cultural zeitgeist, and we all think we know what’s happening there with so much media and artistic coverage. It’s interesting to get a smaller, more intimate take on what it’s like to be immersed as a newcomer to the culture. As Ms. Weiner’s tale unfolds, it pulls the reader along and makes her growth from innocence to awareness parallel with our own journey as readers. As her worry and doubts grow, ours do as well. No company is identified by name, although all are identifiable, but it’s a writing quirk that serves the subject of isolation well as the memoir unfolds.

Feast Your Eyes

by Myla Goldberg

As 2020 forces so many people to desperately re-juggle work and family life, this story of a young photographer raising her daughter may resonate in ways a reader would not have felt six months ago. Much like A Hundred Suns, reviewed below, we know the peril coming and then are immediately thrown back to the start of the story, where Lillian begins, even before Samantha arrives. We also know that Lillian will die in early middle age, so the story is told photo by photo as the show catalogue, with old friends, lovers, Samantha, and Lillian herself speaking from her journals and letters. The unusual approach suits the life story of a photographer and mother always more comfortable watching other people than being on center stage herself. One of the hooks in the story is a Sally Mann backstory with a series of photos of young Sam taken in some degrees of undress (as young children naturally choose to be at home). I really did enjoy this book, and think it is an overlooked gem. The photo controversy makes alone makes it a great book for discussion.

Long Bright River

by Liz Moore

Like The Godmother reviewed below, this book is marketed as a thriller, and it delivers completely on that front (movie rights sold to Amy Pascal—Molly’s Game and The Post—and Neal Moritz—of Fast and the Furious fame). It’s also the story of a family, primarily two sisters. One is a missing drug addict while the other is a cop, while a serial killer appears to be ramping up attacks on women, with some focus on living an honorable life. (I don’t seek out to find books about families and strong women, but lately that theme keeps popping up.) If you were a fan of Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River (as a book or a movie), then this novel should be in the pile by your bed. There are a lot of twists to this story, but it’s all held together with likable characters and good writing. Perfect vacation book—you’ll race through this.

Valentine

by Elizabeth Wetmore

I picked this up from some hot new book list, expecting some easy Texas noir, like Nic Pizzolatto’s debut novel, Galveston. And while the first chapter might start you down that path, Valentine takes a fast turn into the To Kill A Mockingbird territory of racism and justice. But as you settle into this story, it continues to surprise. With many different points of view, this novel gives voice to a lot of strong women, and seems in the end to be a deeper musing on morality, class, and what it means to be a woman in the ’70s oil-boom society that regards the brawn of men as the only valuable commodity. All the women have strong voices and they don’t agree—in fact, they don’t always have the same story to tell the reader about the facts, so there’s book club discussion fodder there as well.

Flight Portfolio

by Julie Orringer

In our era with so many refugees fleeing climate change, war, and corruption, it’s hard not to see the echoes in World War II books like Flight Portfolio. Who’s worth saving and who is not, and how do you live in a world where you cannot save everyone? Based on a real American war effort by a man, Varian Fry, working for the American Emergency Rescue Committee, the book gives you some information that was all new to me. Tasked to save the great artists and writers by helping them escape, the book focuses on a fictional relationship to walk us through the story. I have a pretty high bar for anything that fits into the sub-genre I think of as “heroic escape from the Nazis”—I’m looking for great literature if I’m going to spend more time in this part of history, and this book, meticulously researched, was worth the repeat. Think Schindler’s List but much more consideration of the moral subtleties when you are carefully choosing who you might approach to help escape with very limited time, power, and budget. Reading this the last few months, I imagine some of the story may particularly resonate with health care workers in hard-hit areas of the world, where the same calculus was deployed in allocating resources.

A Hundred Suns

by Karin Tanabe

This was a quick read, as close to a simple beach read as we typically get in these recommendations. Knowing nothing about ’30s Indochine going in, this was an interesting primer on the basics of Michelin rubber and the Michelin industries in French history. The story centers on the American teacher wife of a distant Michelin cousin. It quickly gives you a mystery, gets your heart pounding, then calmly backs up a few months to give you a shot at figuring out what’s happening and why. Another one that’s likely to be snapped up for development as a film or series. If you like Babylon Berlin on Netflix, you’ll enjoy this book.

Greenwood

by Michael Christie

The family saga here is a wild ride, built around the Canadian lumber forests. The book is organized like the rings of a tree, starting in the near future and moving progressively further back to unveil another layer of the family, and then slowly forward again after the midpoint to get us back to the nearby future. The family stories are each a movie unto themselves—rare in a book like this that you aren’t full of questions, wanting to get back to earlier pressing questions. Greenwood keeps you riveted on the current story, even as you see missing pieces fall into place. Full of people I won’t forget, I think it most reminded me of the best of John Irving’s books. Don’t be fooled by the opening sequence—the near future is a bit of climate change dystopia, and if that’s not your kind of book, push through and you will be amply rewarded. This is one of those books you read and you will swear it was a movie you saw—the visuals are so vividly brought to life through the writing, it seems clear you must have seen sets and actors in wardrobe.

Doxology

by Nell Zink

Focused on a a young couple, Pamela and Daniel, in late ’80s NYC who accidentally have a baby while they and their friends live the life of young artists. The story runs all the way up the present, as the multi-generation story that branches off in several directions. Every bit of the story is fun, every sentence is a joy, and while there are many characters, it’s never hard to keep track of them. I think, like many family sagas, the book is about lost innocence, but it’s not nostalgic for a false past. It suggests life is messy and only the people we love really matter—whatever the losses, in the end it was a life well-lived and that’s what matters.

Celine

by Peter Heller

Peter Heller’s books are always a terrific read, and Celine is no exception. (I desperately wanted to mail this book to Jane Fonda and beg her to make a movie of this with herself as the star.) Celine is yet another accidental detective, but she works only to reunite families. Like so many detectives her motivations aren’t entirely pure—she’s got sins in her past for which she feels she should atone. Set against a backdrop of many of the best of American landscapes, Celine and her romantic partner, Peter, have a strikingly great relationship—one that made me realize how few detectives ever have that backstory. As they journey through America on the trail of a missing father, Celine makes reference to other mysteries they’ve tackled, and while this book is a standalone, you may find yourself wishing they were their own books. I think those throwaway references, never fully explained, add to the intimacy of the book—like the shorthand you have with a good friend of long standing. If you end up liking this, while the characters do not repeat, all his books are well worth your time. (Our family all liked The Dog Star so much, we discovered our older son had appropriated our copy as part of his permanent library when he left for college.)

Little Eyes

by Samantha Schweblin

If you read Schweblin’s Fever Dream, you know she’s not a science fiction writer. If you didn’t I feel the need to tell you this book isn’t SciFi or an alternate reality. Only one detail differs from our modern day—a consumer product known as a kentuki exists. Translated from the Spanish, this book takes us all over the world in the modern day as people open their kentukis. Each one is good for one partnership only, with one person having physical possession of the small, furry companion, while another person, anonymously, controls the (unspeaking), motorized, webcam-containing kentuki. While it reads like dystopian fiction, we see how the kentukis fill a void, sometimes unhealthily, for lonely people all over the world. What happens when you share all of your life with a stranger? Are you more connected or more isolated? A really interesting look at our current society and social media, shown through a plausible extension of our current set of social network choices.

Men We Reaped

by Jessamyn Ward

I’m a big fan of Ms. Ward’s fiction, and I knew this book covered her life in Mississippi. I bought this a few years ago to better understand how a writer’s life impacts their art, and for an honest account of life under the American poverty line, although, as many book buyers can relate, it took a while to percolate up to the top of the pile. Keeping in mind I’ve always been a Faulkner fan, the American South has always seemed fascinatingly hard to understand. I lurk around the edges, scooping up authors of fiction and non-fiction who might help me understand. It turns out there is no better guide than Jessamyn Ward. With two National Book Awards under her belt already, she’s a writer who is part of the American canon, and this book is a riveting read, although it is inevitably tragic as she loses five men in her life, one by one, in as many years—a loss unimaginable to most Americans. While the book was written in 2013, it’s particularly interesting now to listen to now, as discussions of social inequality, racism, and sexism are front and center in the headlines. This is a book about managing to live and celebrate life while also reeling from unremitting grief.

The Godmother

by Hannelore Cayre

This book is destined to be a movie, and the rights have already been sold, so read it fast. It’s a short book, a very quick read, translated from the French. It’s ostensibly a Breaking Bad scenario—an aging, regular woman protagonist has an economic need, sees an opportunity in the drug trade, and takes it. On that level the story is a lot of fun—a fast-paced, action-packed thrill-ride. You can leave it there and walk away. (This book is so short, it wouldn’t fill a San Diego to New York flight for most readers. In fact, it’s so captivating and so short, if you start one night you may kip sleeping to finish.) But it spends just enough sidelong glances down dark alleys not taken to show how the systemic prejudice against the poor, foreign, and even women breaks down overall society, so you don’t have to log it in the guilt pleasures column.

Claire Dewitt and the City of the Dead

by Sara Gran

I picked this up thinking it was a detective novel set in New Orleans, but it’s a book about a lot of different mysteries. Claire’s solving one crime now, while her life is built around a long-gone missing childhood friend, and there’s a wild meta discussion about what it means to be a detective and a mystery. The writing is top-notch, and in true Southern Gothic and noir traditions, things are bad, getting worse, and yet Claire doggedly tries to alleviate human suffering as a result of the unknown as best she can, while carrying her own pain—all of that in a post-Katrina New Orleans. Satisfying read for mystery lovers, but the book has such a love of language, it’s great for people who love a little quality. It’s an unusual book, and as you can see from our link above, there aren’t many mainstream reviews. This one is a hidden gem from about 10 years ago (now there a few others in the series). It’s a book you’ll love or hate for its experiments—it defies categorization, but it suits New Orleans and there’s no denying Sara Gran’s writing talent. I’ve yet to have anyone dislike it, but it’s odd enough that it would be a tough book for book club to pick apart. For the adventurous reader.

2021 LYON

2021 LYON